Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...- Telephone: 609 924 2210

- Home

- My Account

- Gift Certificates

- View Cart

Blue Cheese - History and production

Posted by The Cheese Man on 13th Aug 2019

The discovery and production of Blue Cheese.

As I told some of you who came into the store in the last week or so, I was struggling to determine what I was going to send you this week around the theme of Blue Cheese. Something about how it was discovered all those years ago? Or maybe something more technical around the making of the cheese? Hmmm, hmmm. So here it is. I couldn’t decide between the two and now there is a piece about both.

We do not know exactly when (estimates range from 85 BC to 1250 BC – I tend to place it around 1000 BC, just because), but we do know where the Blue Cheese mold was discovered. It is generally accepted that it was in the Roquefort region of France and more specifically in one of the many caves that dot the landscape there. There are many different myths around the discovery of the blue cheese mold (ranging from a shepherd being visited by an angel, who instructed him to put cheese in a particular cave to a drunken cheese maker forgetting his cheese in a cave). However, here is the one that I typically opt for when explaining how the mold was discovered.

A shepherd leads his flock through the country side in what is now the National Parc of Grands Causes in the Aveyron region. In the park is a limestone formation called Combalou with on its crumbled slope the village of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon. The shepherd takes shelter in a cave - perhaps there was a storm moving in – and because it is lunch time puts a piece of bread right next to a piece of sheep’s milk cheese on a rocky outcrop. For whatever reason – perhaps there was something amiss with the animals – the shepherd leaves the cave. Only to come back a couple of weeks later. Had the animals wandered into the same area and did the shepherd recognize the cave with the lunch in it? We will never know, but upon entering the cave, the shepherd sees that a blue mold has formed on the outside of the bread. As the bread and the cheese were touching the mold had spread onto the cheese. Biggest question we always have with this is: What made the shepherd think that it was a good idea to eat the cheese? Good thing they did, however, and even better that they liked what they tasted. For the longest time, the cheese from Roquefort was made by putting bread in the cave, let the mold form, then scrunch up the bread and smear it all over the outside of a cheese. Perhaps that is why some doctors to this day tell Celiac patients not to eat blue cheese. We have long ago been able to generate the mold in a laboratory and it is now identified as Penicillium Roqueforti. No bread is involved.

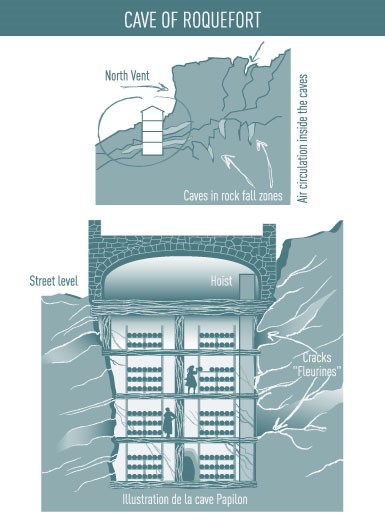

So, although it is perfectly possible to make a Roquefort cheese outside the caves in the Grands Causes region of France, the rules that govern the making of Roquefort cheese specify that – apart from being made with raw Lacaune sheep’s milk – the cheese has to age in the caves of Roquefort. That is why only a limited amount of Roquefort cheese can be made. The company with the biggest cave capacity, Societee Bee, is therefore the biggest Roquefort producer, followed by a company called Papillon with the company Carles a distinct third. Below is a graphic representation of the Papillon caves. Cracks that formed in the limestone, called ‘fleurines’, ensure that a constant temperature of around 48 degrees F is maintained with a 95% humidity. The ‘fleurines’ work like chimneys pulling cold and moist air in and pushing warm air out.

The process of making a blue cheese starts the same as any other cheese. Milk is poured into a vat and starter cultures and rennet are added. The difference is that for a blue cheese, a blueing agent, usually Penicillium Roqueforti, is introduced at this stage too. There are only a very limited number of cheeses that rely on the naturally occurring blue spores in caves to do the blueing. Once the curds have formed, the whey is removed and the curds allowed to drain overnight. The following morning, the curd is cut into blocks to allow further drainage before being milled and salted. The salted curd is then fed into cylindrical molds. The molds are placed on boards and flipped daily to allow natural drainage and even distribution of the whey for 5 or 6 days. As the cheese is never pressed, it exhibits the flaky, open texture required for the important blueing stage. After this aerobic aging, the cylinders are removed and the outside of each cheese is sealed by smoothing (to form a natural rind like Stilton) or wrapping (typically in aluminum foil like Cashel, Roquefort, Bleu d’Auvergne) to prevent any air entering the inside of the cheese. At about 6 weeks, the cheese is ready for piercing with stainless steel needles. This allows air to enter the body of the cheese and create the magical blue veins and pockets associated with the “Blues”.

When considering putting a blue cheese on your cheese board, please ensure that your guests are aware that this cheese is the most potent and should be eaten last. Blue cheese does a real number on your taste buds and will prevent any subsequent cheese from making any impression at all. Blue cheeses are natural companies to sweet wines or fortified wines like Port and also go really well with sweet fruits. Next time you are in the store ask me about my favorite dessert!!

Blue cheeses currently available in the store: Stilton, Shropshire, Point Reyes Blue, Great Hill Blue, Roquefort (Societe Bee), Cambozola Black Label, Lancaster Blue (very strong), Bleu d’Auvergne, St. Agur, Huntsman.